The Fermented Gang: Avengers in Your Plate

As a budding alchemist, for almost two years I kept a small, airtight jar of umeboshi in my fridge. No, it’s not some kind of miniature samurai chocolate, but rather a type of pickled plum, a great classic in Japanese cuisine. During that time, I was on the lookout for the slightest trace of the development of a disgusting greenish mold, wonky and viscous filaments, or other fascinating microbial activity that could feed my curiosity about natural phenomena. Nay, nada, “rien pantoute,” as my cousins in Québec would say! So, I had to try the ultimate experience that would have made even a Marvel superhero pale: taste them! After a few long hesitations, with the tip of my tongue, the fear of intoxication subsided as soon as my taste buds were stimulated. These little shriveled prunes honoured their ancestral reputation as natural health gems. With them, my onigiri (rice balls wrapped in leaves of nori seaweed) were a delight, and I didn’t wind up in the emergency room!

To each their own tastes, you might say; however, we all have our guilty pleasures when it comes to fermented food and drink. Consider cheese, sauerkraut, bread, kimchi, miso, wine, vinegar, kefir, yogurt, lassi, nuoc mam, beer, tea, condiments, kombucha, etc., For sure, you’ll find yourself in these.

Ferment to Multiply the Power!

You guessed it, the object of this praise is none other than fermentation, which, unlike the masked Avengers of our millennial generation’s screens, has contributed to the survival of various human civilizations for thousands of years. Today, nearly 5,000 different products are made through traditional and industrial fermentation—including cabbage, soybeans, corn, fish, garlic, beans, etc.—which can represent up to 40% of all food consumed in some regions of the world.

Fermentation includes three main types—alcoholic, lactic, and acetic (vinegar)—and rely on microorganisms (yeast and bacteria) to operate in anaerobic biochemical transformations, degrading organic matter, releasing energy, and rendering the physicochemical environment unfit for the development of pathogenic bacteria. In the end, fermented foods can not only be preserved for long periods, but also acquire original organoleptic and nutritional properties which are multiplied tenfold; this makes them superfoods. Nutrients and antioxidants are created and multiplied, and they become highly bioavailable. Their new nutritional value and associated physiological benefits also make them “functional” foods.

Take the example of the incomparable concentrations of vitamin K2 in nattō (fermented soybeans), a must in the list of natural solutions for osteoporosis; between grape juice and red wine, trans-resveratrol (a polyphenol antioxidant) is multiplied by 10; vitamin C and isoflavones, of cabbage and soybeans respectively, are tripled during their fermentation; etc.

Fermented foods have their nutritional profile rebalanced with reduced sugar content, and their protein and polyunsaturated fatty acids increased. Digestibility is increased through the probiotic effect, which also improves intestinal flora, provides vitamins, and supports the immune system. Moreover, fermentation tends to acidify foods, making minerals easier to absorb. Finally, fermentation eliminates pathogenic organisms through bacteriocins or lactic acid; it inhibits antinutritional substances such as lactose or potentially harmful fungal toxins, cassava cyanide, or phytic acid in vegetables and grains that limits calcium, magnesium, and zinc absorption.

For several years now, the natural health-product industry has promoted fermented “superfoods” that are predigested and boosted, offering valuable health benefits. Today, we find powders that include fermented turmeric or ginger that can garnish drinks, smoothies, sauces, or various culinary preparations. You can make yourself a fermented ginger drink at home, as the various recipes are very simple to prepare (refer to the one at the end of the magazine). They can even be an educational experience for children!

Ginger and Turmeric: Super Spices

Let’s briefly recall the valuable properties of ginger and turmeric, the universal stars of spice cabinets and natural remedies. Firstly, Burmese tradition says that the universe was created from turmeric—nothing less! From a more rational perspective, the rhizomes of these cousins of the Zingiberaceae botanical family have similar properties:

- Powerful antioxidant and anti-inflammatory;

- Lipid-lowering (lower cholesterol or triglycerides);

- Antiangiogenic and anticancer;

- Hepatoprotective;

- Antimicrobial; and

- Neuro- and cardioprotective.

Specifically, ginger (Zinziber officinale) also acts as a general tonic (notably sexual and cerebral, and slightly cardio), adaptogen, blood thinner, detoxifier, nausea remedy for motion sickness, and digestive aid. Ginger also helps calm morning sickness during pregnancy, can be prepared in a warming and soothing herbal tea for sore throats, or fight against migraine headaches.

Turmeric (Curcuma longa), also adds purging properties (promoting bile flow), and others which are low-dose antiulcer, anti-Alzheimer (destroying amyloid plaques and blocking their accumulation), and antiatherogenic (limiting vascular risks). Note that turmeric has poor intestinal bioavailability, which can be greatly enhanced by the addition of fat and especially of black pepper (Piper nigrum), thanks to piperine, of which the therapeutic dose is 5 mg for every 500 mg of turmeric standardized to 95% curcuminoids.

These plants are already powerful remedies, thus when fermented, they only become more powerful and effective. Let’s illustrate this with some notes on research that show the health benefits of fermentation of these two rhizomes…

A study conducted in 2010 shows how fermentation of ginger (among others forming the 6-gingerdiol) not only multiplies its anti-inflammatory properties, but when mixed with red yeast rice was also found in experiments to be much more effective against cholesterol.

A study conducted in 2015 on fermented turmeric shows its considerable impact on not only reducing the risk of liver-cell injury, but also that of heart, muscle, and kidney. Furthermore, research has shown that fermented turmeric antioxidants minimize formation of fat, improving body composition and reducing obesity.

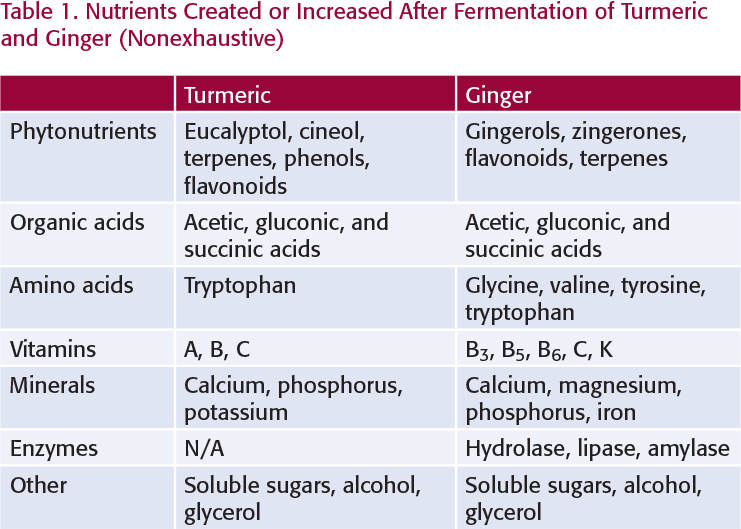

Other recent studies emphasize the enhancing properties of ginger and fermented turmeric; for example, several forms of curcuminoids develop with turmeric, among which the whiter-pigmented tetrahydrocurcumin is far more bioavailable than other curcuminoids. Moreover, an increase in phenols (reports of up to 1:40!), organic acids and other synergistic substances are shown in the following table.

Turmeric and ginger have a well-established medicinal reputation. As for fermentation, its universal and immemorial usages not only inspire confidence, but also find their legitimacy in the observations of modern science, which validates the tremendous potential fermentation brings to health. Mix everything, and you get two fermented champions in the pantheon of superfoods, always ready to make your beverages and dishes a true healthy and gustatory adventure.

Finally, as the good-natured Gallic that I am, I also invite you to taste each day—to the extent possible and within reason—all things fermented, whether it be a sourdough baguette, sauerkraut, raw cheese, or glass of red wine!

References

- Anand, P., et autres. « Bioavailability of curcumin: Problems and promises. » Mol Pharm. 2007 Nov-Dec; 4 (6):807-18.

- Branger. A. « Fabrication de produits alimentaires par fermentation : L’ingénierie. » Techniques de l’ingénieur, F3501 (2004): 1–15.

- Chen, C.C., et autres. « Enhanced anti-inflammatory activities of Monascus pilosus fermented products by addition of ginger to the medium. » Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Vol. 58, N° 22 (2010): 12006–12013.

- Erika, J.J., et autres. « Hot spices influence permeability of human intestinal epithelial monolayers. » The Journal of Nutrition, Vol. 128, N° 3 (1998): 577–581.

- Morel, J.M. Traité pratique de phytothérapie. Escalquens : Grancher, 2008, 618 p., ISBN 978-2-7339-1043-6.

- Mohamed, S.A., et autres. « Influence of solid state fermentation by Trichoderma spp. on solubility, phenolic content, antioxidant, and antimicrobial activities of commercial turmeric. » Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, Vol. 80, N° 5 (2016): 920–928.

- Saleh, R.M., et autres. « Solid-state fermentation by Trichoderma viride for enhancing phenolic content, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities in ginger. » Letters in Applied Microbiology, Vol. 67, N° 2 (2018): 161–167.

- Jihye, K., et autres. « Radical scavenging and anti-obesity effects of 50% ethanol extract from fermented Curcuma longa L. » Journal of the Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition, Vol. 44, N° 2 (2015): 281–286.

- Katsuyama, H., et autres. « Promotion of bone formation by fermented soybean (Natto) intake in premenopausal women. » Journal of Nutritional Science and Vitaminology, Vol. 50, N° 2 (2004): 114–20.

- Khajuria, A., et autres. « Piperine modulates permeability characteristics of intestine by inducing alterations in membrane dynamics: influence on brush border membrane fluidity, ultrastructure and enzyme kinetics. » Phytomedicine, Vol. 9, N° 3 (2002): 224–231.

- Sang-Wook, K., et autres. « The effectiveness of fermented turmeric powder in subjects with elevated alanine transaminase levels: A randomized controlled study. » BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Vol. 13 (2013): 58.

- Shoba, G., et autres. « Influence of piperine on the pharmacokinetics of curcumin in animals and human volunteers. » Planta Medica, Vol. 64, N° 4 (1998): 353–356.

- Gagné, L.M. « Les aliments fermentés démystifiés. » Passeport Santé.Net. · https://www.passeportsante.net/fr/Actualites/Nouvelles/Fiche.aspx?doc=aliments-fermentes-demystifies_20110601 · Publié le 2011-06-01.

- Léveillé, P. « Les aliments fermentés, mine d’innovations et trésors pour la santé. » INRA : Science & Impact. · http://www.inra.fr/Grand-public/Alimentation-et-sante/Tous-les-magazines/Aliments-fermentes-mine-d-innovations-tresors-pour-la-sante · Mis à jour le 2015-08-12.

Guillaume Landry, MSc, Naturopath

Guillaume Landry, MSc, Naturopath

A native of the Jura mountains of eastern France, he shares

his passion for the wonders of nature and natural medicine.

Stores

Stores